Before You Change Your Name, Answer This

Do you know what your name means?

Who chose it?

Why did they choose it?

Was it cultural? Biblical? Ancestral? Popular at the time? Pulled from television? Or family member? Or Friend of Family?

Have you ever researched its origin?

If you have a child — what does their name mean? And why did you choose it?

Before reclaiming anything, you should understand what you’ve already been resonating with.

Most people never pause long enough to ask these questions. A name becomes background noise. It’s printed on documents, repeated in classrooms, signed on contracts — but rarely examined.

Yet in indigenous societies, names were not casual.

They reflected circumstance.

They reflected character.

They reflected responsibility.

They reflected covenant.

Sometimes they reflected what that child would grow into.

Many of Us Were Not Named With Intention

Many of us were not named within a preserved system of psychological or spiritual intention.

That does not mean our parents did not care.

It means they were navigating the effects of colonization and denationalization.

When a people are stripped of political identity, cultural continuity, and ancestral systems, naming loses structure. It becomes detached from function.

And when naming loses structure, it loses responsibility.

Most families were never taught the power of intention in naming. They were never taught that a name can reflect disposition, covenant, or projected responsibility.

Naming became preference.

It became trend.

It became familiarity.

We do still see intentional naming preserved in some religious traditions — where names reflect attributes of God, prophetic meaning, or spiritual aspiration.

But broadly speaking, colonization interrupted indigenous systems that named according to psychology, celestial orientation, and ancestral function.

Denationalization did not only remove socio-political status.

It disrupted identity transmission.

(Identity transmission is the sociological and psychological process of passing down shared values, traditions, behaviors, and self-perceptions from one generation to the next, often within families or cultural groups. It ensures continuity of identity through cultural socialization, such as teaching language, religion, or food practices, which shapes how individuals define themselves.

Reclaiming identity requires restoring intention.

Not as rebellion.

Not as performance.

But as responsibility.

If someone chooses to change their name, it should not be cosmetic.

It should be conscious.

What an Indigenous Name Reading Actually Is

Within our tribe, there are generally three paths when someone begins reconsidering their name:

Some keep their birth name and add an indigenous appellation — Xi, Amaru, Ali, El, Bey.

Some already have a name in mind that resonates.

Others request a name reading.

A name reading is not fortune telling.

It is not role-play.

It reflects inherent psychology — the pattern you were born carrying.

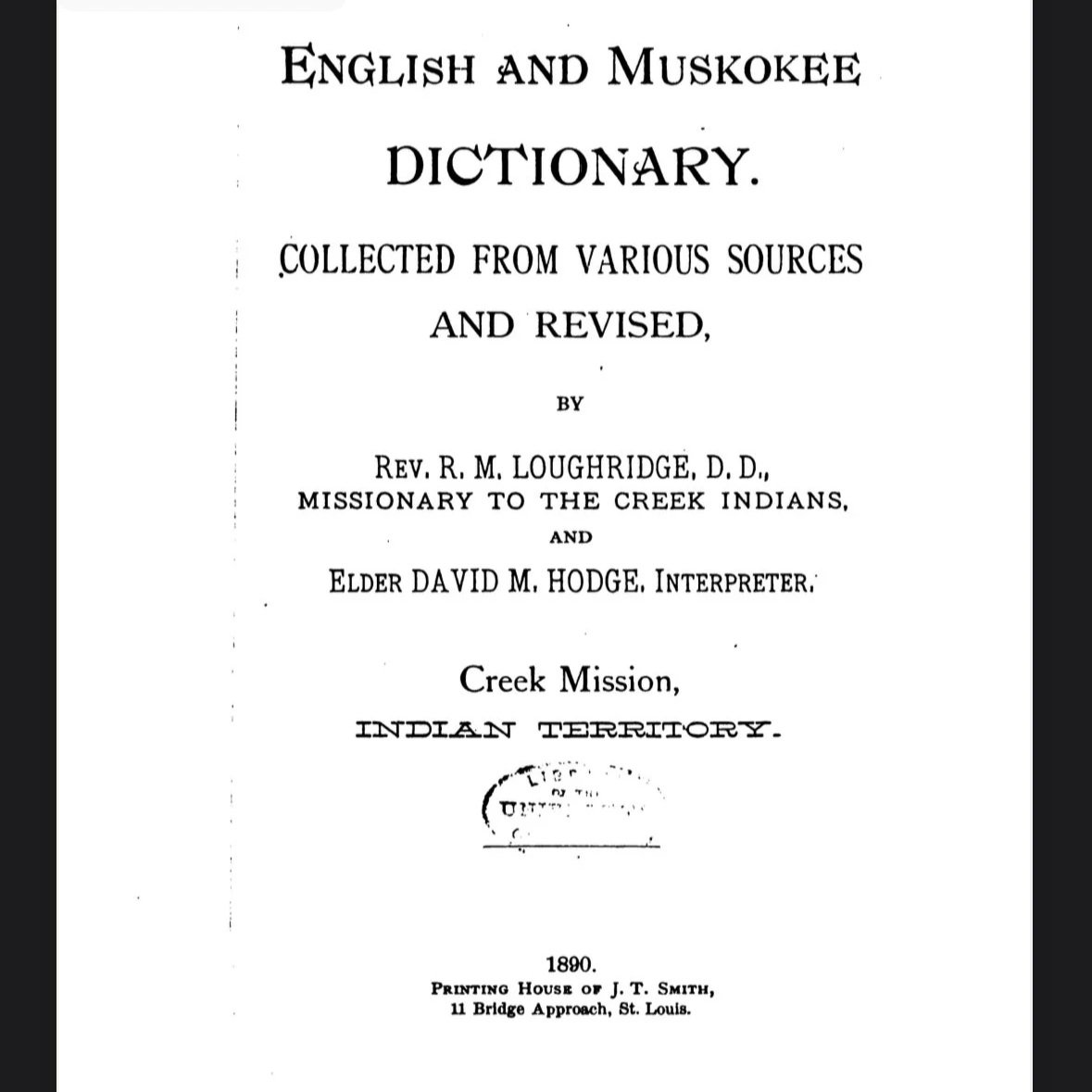

Names are extracted from Indigenous linguistic streams, including K’iche, Xi hieroglyphic systems, and Hitchiti traditions of the Southeast. Sound, structure, and meaning are considered together — not as aesthetic choice, but as alignment with ancestral psychology and function.

It draws from indigenous astronomical and ancestral systems where celestial bodies were understood to influence psychological dispositions. Modern planetary names like Jupiter or Mars are Greco-Roman labels. Our system retains indigenous ancestral names tied to those same forces.

The reading identifies:

core disposition

strengths

tendencies

and how those energies express themselves

Often, people recognize themselves immediately.

Because the pattern was already there.

You Will Not Be the Only One

13 primary ancestors/psychological profiles source: Restitution Manual-Group Dissertation Amaru Xi Ali et al

This is important.

You will not be the only one with that ancestral designation.

Multiple members may carry the same psychological marker.

Why?

Because psychology repeats.

In older village systems, this was understood.

The community knew:

Who carried warrior energy.

Who stabilized resources.

Who mediated conflict.

Who expanded ideas.

Who protected boundaries.

Who unified people.

Names reflected function and disposition — not uniqueness for ego’s sake.

The goal is not to become rare.

The goal is to become aware.

Restoring the Village

When a community loses its naming systems, it loses psychological literacy.

People expect the wrong things from the wrong people.

Gifts are misapplied.

Leadership becomes confused.

Conflict increases.

Restoring indigenous naming restores awareness.

When the village understands:

Who builds.

Who strategizes.

Who nurtures.

Who protects.

Who expands.

Who binds.

Alignment becomes easier.

Responsibility becomes clearer.

Cooperation becomes more natural.

Restoring the name is one layer of restoring the village.

Xi and Amaru

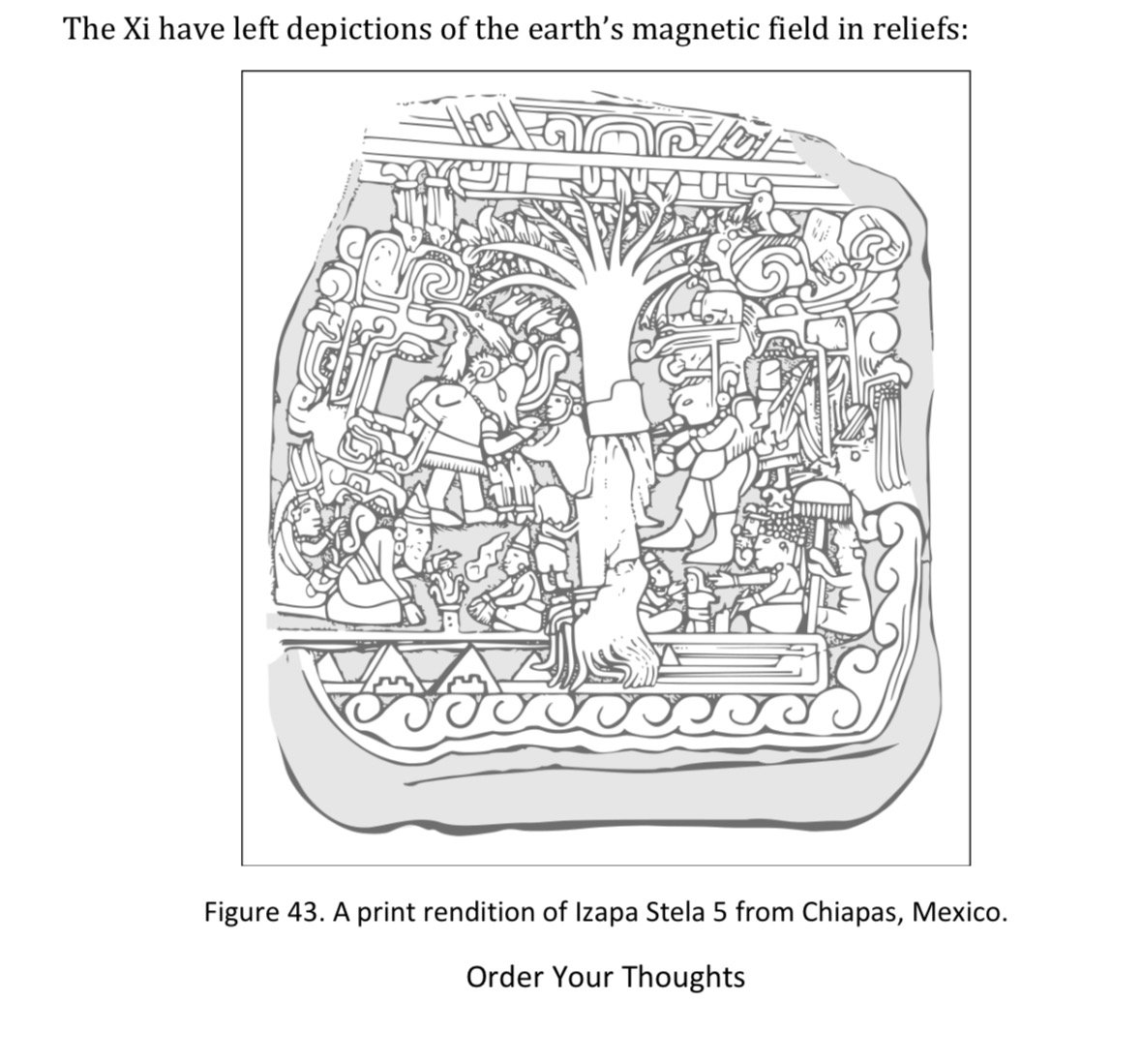

Xi means The People of the Tree.

The Tree represents the living axis — roots below, branches above. It symbolizes structure, continuity, covenant, and life sustained across generations.

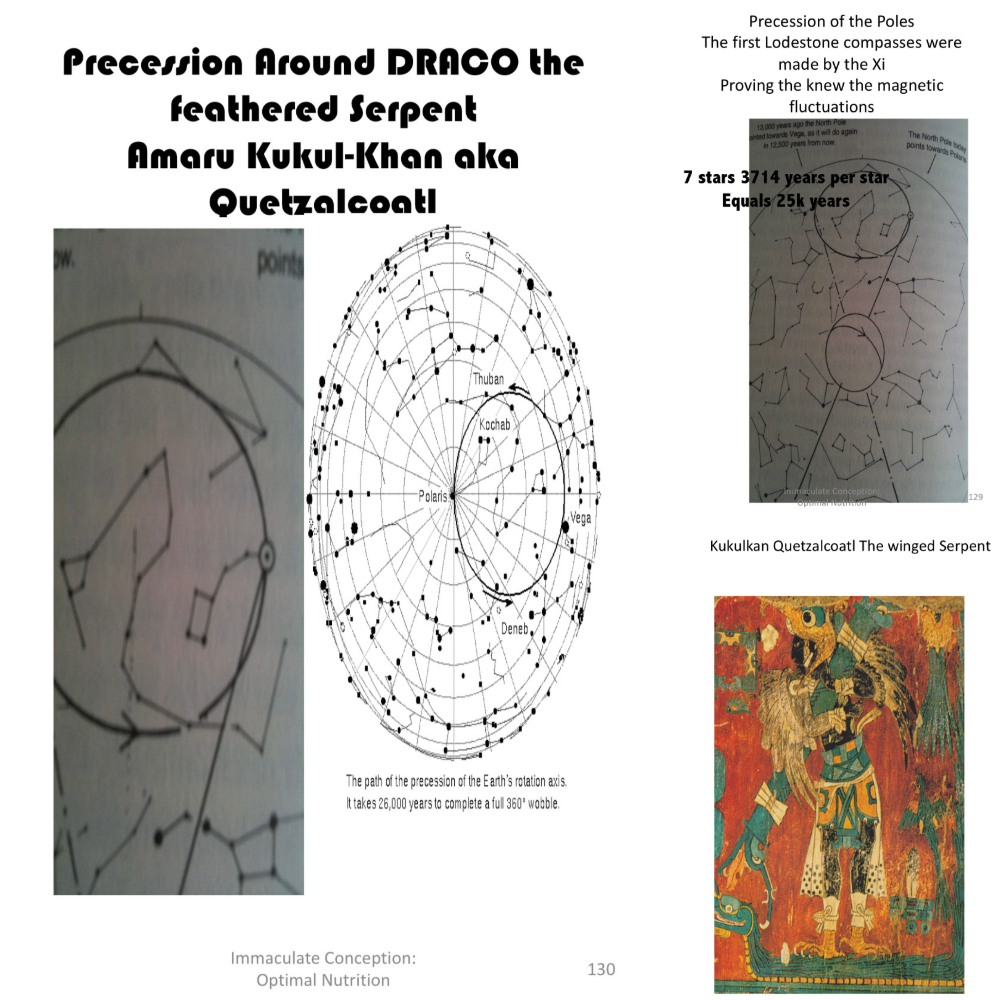

Amaru is associated with the serpent principle — known in Mesoamerican memory as Kukulkan or Quetzalcoatl, the feathered serpent.

Source: Immaculate Conception. Amaru Xi-Ali

Astronomically, this serpent aligns with Draco — the circumpolar constellation that does not set in the northern sky. It circles the pole star. Through the precession of the equinoxes — the Earth’s 26,000-year axial wobble — the pole shifts from star to star across long cycles, yet Draco remains present in that rotation.

The serpent does not disappear with the seasons.

It endures.

Xi-Amaru speaks to rooted people who remember.

People aligned with continuity across cycles — not trends, not moments, but time itself.

Continuity Across the Southeast

The Xi-Amaru lineage is often reduced to what textbooks label “Mesoamerican.” That framing is incomplete.

The mound-building civilizations of North America — including those of the Southeast — operated within structured cosmological and naming systems tied to earthworks, celestial cycles, and communal function.

Among the Hitchiti (Muscogee) peoples of the Southeast, identity and responsibility were not isolated from land or sky. Naming carried weight. Function within the village was understood. Roles were not random.

What modern narratives separate into regions once existed within broader hemispheric continuity.

The same astronomical awareness that informed pyramid construction informed mound construction. The same orientation to celestial cycles informed naming systems. The same understanding of magnetic fluctuation and seasonal alignment informed community structure.

In our Indigenous Name Readings, we incorporate linguistic elements drawn not only from K’iche and Xi hieroglyphic traditions, but also from Hitchiti and Southeastern Indigenous language streams. This reflects continuity — not fragmentation.

The system is not imported.

It is remembered.

When we speak of Xi-Amaru, we are not speaking of a disconnected ancient culture.

We are speaking of a memory system carried across generations — from pyramid to mound, from serpent to earthwork, from sky alignment to village responsibility.

Restoring indigenous naming restores that continuity.

Understanding Indigenous names requires understanding this continuity throughout the American South and beyond.

For those seeking rigorous historical grounding, we strongly recommend the scholarship of Dr. Amaru Xi-Ali, particularly his book:

This work documents Indigenous presence, misclassification, and survival in the Americas and provides essential context for identity restoration.

(A link to purchase will be provided separately.) https://www.arnagovernment.org/store/p157/EBOOK-They_Lied_About_the_Slave_Trade-An_Indigenous_review.html

Identity Does Not Erase Lineage

Choosing an Indigenous name does not require abandoning your family name.

Awareness requires integration, not erasure.

Many families — particularly among descendants of American chattel slavery (often referred to as ADOS or FBA, Foundational Black Americans) — have genealogical ties to land allotments, land patents, and property transfers that were issued, inherited, misclassified, lost, or left unclaimed through generations of unawareness.

These records exist.

Land patents are federal instruments.

Allotments were documented.

Transfers were recorded.

In many cases, families were separated from the knowledge of what was issued in their name.

When someone becomes the first in their bloodline to move consciously — to research, to restore, to rename — that awareness will stand out in the lineage.

But restoration does not discard documentation.

Your ancestral surname may still be tied to recorded land patents, allotments, or property instruments.

For this reason, name restoration should move alongside genealogical research — not replace it.

Within our broader framework, genealogy includes structured land patent research tied directly to documented family lines.

Identity restoration, record recovery, and legal positioning must move together.

Changing your name is a declaration of awareness.

Tracing your lineage is preservation of claim and continuity.

Both matter.

Before You Order a Name Reading

Start with your current name.

Research its origin.

Understand its language.

Ask your family why it was chosen.

Reflect on the energy you’ve already lived under.

If you have children, do the same for them.

This process is not about discarding your past.

It is about becoming conscious of it.

If you are ready to move from curiosity to clarity — the Indigenous Name Reading is the next step.

It will identify your innate ancestral psychology, reveal the pattern potentials you were born carrying, and provide configuration pathways aligned with that awareness.

If you are ready to move from curiosity to clarity, request your Indigenous Name Reading below: